User’s Guide, Chapter 3: Pitches, Durations, and Notes again¶

Now that you’ve made a couple of Note objects, it’s time to dig a

little deeper into what makes a Note really a Note, namely,

music21.pitch, and music21.duration objects.

The Pitch object¶

Since we’ve already covered Note objects,

Pitch objects will be a breeze. Just like how

the Note object is found in the note module, the Pitch

object is found in the pitch module.

Let’s create a Pitch. Like we did with Notes, just class the

class with a note name, such as B with the optional symbols for

sharp or flat, (# or - respectively).

You can put an octave number after the name (4 = low treble clef), but you don’t have to:

from music21 import *

p1 = pitch.Pitch('b-4')

Here we’ll use a more abstract variable name, p1 for our first

Pitch, just in case we change the pitch later (via .transpose()

or something else).

Just like we saw with Notes there are a lot of attributes (a.k.a.

properties; we’ll use the term interchangeably for a bit before we talk

about the difference) and methods that describe and change pitches. The

first three will be old hat from Note objects:

p1.octave

4

p1.pitchClass

10

p1.name

'B-'

p1.accidental.alter

-1.0

Here are two more that you can use. The first is pretty

self-explanatory. The second gives the value of the Pitch in the

older, “MIDI” representation that is still in use today. It’s a number

between 0 and 127 where middle C (C4) is 60 and C#4/Db4 is 61, B3 is 59,

etc.

p1.nameWithOctave

'B-4'

p1.midi

70

Most of these attributes can be changed (they are “settable properties” in Python speak).

When an attribute is set, the Pitch object changes whatever is

necessary to reflect the new value:

p1.name = 'd#'

p1.octave = 3

p1.nameWithOctave

'D#3'

And our familiar .transpose() method also appears on Pitch as

well. Remember that p1 is now a D#:

p2 = p1.transpose('M7')

p2

<music21.pitch.Pitch C##4>

Notice that at the command line, just printing the variable name gives

you the representation <music21.pitch.Pitch C##4>. You can also get

this by typing repr(p2).

So, there’s really nothing new about Pitch objects that you didn’t

already know from learning about Notes. So why the two different

objects? It turns out, they are so similar because actually every

Note object has a Pitch object inside it (like the monster in

Alien but more benign). Everything that we did with the note.Note

object, we could do with the note.Note.pitch object instead:

csharp = note.Note('C#4')

csharp.name

'C#'

csharp.pitch.name

'C#'

csharp.octave

4

csharp.pitch.octave

4

But pitch objects have a lot more to offer for more technical working,

for instance, Pitch objects know their names in Spanish:

csharp.pitch.spanish

'do sostenido'

Notes don’t:

csharp.spanish

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-16-a0f0e2502262> in <module>

----> 1 csharp.spanish

AttributeError: 'Note' object has no attribute 'spanish'

Here are some other things you can do with Pitch objects. Get the sharp printed nicely:

print(csharp.pitch.unicodeName)

C♯

Get some enharmonics – these are methods, so we add () to them:

print( csharp.pitch.getEnharmonic() )

print( csharp.pitch.getLowerEnharmonic() )

D-4

B##3

By the way, you know how we said that you shouldn’t have a variable

named pitch because there’s already a module named pitch?

You might wonder why Note objects can have an attribute named

pitch without causing any problems. It’s because the .pitch

attribute is always attached to a Note , so it’s never used

without a prefix of some sort (in this case, csharp.pitch ), and

that’s enough to prevent any trouble.

So far, it looks like Pitch objects can do everything Note

objects can do and more. So why do we need Note objects? It’s

because they also have Duration attributes, as we’ll see in the next

section. Without a Duration attribute, you cannot put an object into

a Measure or show it on your screen.

Carving time with Duration objects¶

For a Note to occupy musical space, it has to last a certain amount

of time. We call that time the Note’s

Duration. Duration objects are

ubiquitous in music21. Nearly all objects have, or can have, a

Duration. A Duration object can represent just about any time

span.

Duration objects are best used when they’re attached to something

else, like a Note or a Rest, but for now, let’s look at what we

can do with them on their own.

Duration objects reside in the duration module. When you create

a Duration object, you can say what type of duration you want it to

be when you create it.

Here we’ll create the duration of a half note:

halfDuration = duration.Duration('half')

The string “half” is called the “type” of the Duration. Music21

Durations use the common American duration types: “whole”, “half”,

“quarter”, “eighth”, “16th”, “32nd”, “64th”. Note that for durations

shorter than an eighth note, we use numbers instead of spelling out the

whole name of the Duration type. Music21 also supports less commonly

used types such as “breve” (2 whole notes), “longa” (4 whole notes), and

“maxima” (8 whole notes) and on the other side, “128th”, “256th”, etc.

down to “2048th” notes. (Some of these very long and very short notes

can’t be displayed in many musical notation systems, but it’s good to

know that we’re ready when they are).

The other standard way of creating a Duration is by passing it a

number when it is created. That number represents how many quarter notes

long it is. So we could have created our half note Duration by

saying 2 or 2.0. But we can also create Durations that

aren’t exactly “whole”, “half”, “quarter”, etc. Let’s create a dotted

quarter note, which is 1.5 quarter notes long:

dottedQuarter = duration.Duration(1.5)

As with the Pitch and Note objects we’ve already seen, there are

a bunch of attributes that Duration objects have. The most important

one is .quarterLength. The

quarterLength of our

dottedQuarter variable is of course 1.5: we set it to be. But just

as importantly, the halfDuration object also has its quarterLength

set:

dottedQuarter.quarterLength

1.5

halfDuration.quarterLength

2.0

The .type attribute tells you what general type of Duration you

have:

halfDuration.type

'half'

dottedQuarter.type

'quarter'

The type attribute cannot be everything that describes the

Duration, there has to be some place where music21 keeps track of

the fact that the dottedQuarter variable has a dot (otherwise it

wouldn’t have a quarterLength of 1.5). You’ll find the attribute

called .dots:

halfDuration.dots

0

dottedQuarter.dots

1

The attributes of dots, type, and quarterLength are actually

special attributes called “properties”. A property is an attribute that

is smart in some way. Let’s change the number of dots on our

dottedQuarter object and see what happens to the quarterLength

property:

dottedQuarter.dots = 2

dottedQuarter.quarterLength

1.75

dottedQuarter.dots = 3

dottedQuarter.quarterLength

1.875

dottedQuarter.dots = 4

dottedQuarter.quarterLength

1.9375

Or let’s change the quarterLength of the dottedQuarter and see what

happens to the type and dots:

dottedQuarter.quarterLength = 0.25

dottedQuarter.type

'16th'

dottedQuarter.dots

0

QuarterLengths are so important to music21 that we’ll sometimes

abbreviate them as qL or qLs. Almost everything that is measured

in music21 is measured in qLs.

Music21 can also deal with other quarterLengths such as 0.8, which

is 4/5ths of a quarter note, or 1/3, which is an eighth note triplet.

(For this reason, users compiling spreadsheets or other text-based

output should expect to find the occasional quarterLength expressed

as a Fraction.)

(You can go ahead and make a triplet or other

Tuplet, but we’ll get to triplets,

including tips for manipulating a Fraction in Chapter 19).

Back to Notes¶

So now you can see the advantage of working with Note objects: they

have both a .pitch attribute, which contains a Pitch object, and

a .duration attribute, which contains a Duration object. The

default Pitch for a Note is C (meaning C4) and the

default Duration is 1.0, or a quarter note.

n1 = note.Note()

n1.pitch

<music21.pitch.Pitch C4>

n1.duration

<music21.duration.Duration 1.0>

But we can play around with them:

n1.pitch.nameWithOctave = 'E-5'

n1.duration.quarterLength = 3.0

and then the other properties change accordingly:

n1.duration.type

'half'

n1.duration.dots

1

n1.pitch.name

'E-'

n1.pitch.accidental

<music21.pitch.Accidental flat>

n1.octave

5

We already said that some of the attributes of Pitch can also be

called on the Note object itself. The same is true for the most

important attributes of Duration:

n1.name

'E-'

n1.quarterLength

3.0

Let’s change the quarterLength back to 1.0 for now:

n1.quarterLength = 1.0

Notes can do things that neither Pitch or Duration objects

can do. For instance, they can have lyrics. Let’s add some lyrics to

Notes. You can easily set Lyric objects

just by setting the lyric

property. (For reference, the lyric attribute is actually an

attribute of GeneralNote, which is a “base

class” from which the Note class “inherits”. In other words, the

Note class gains the lyric attribute from GeneralNote. But

that’s not too important.)

otherNote = note.Note("F6")

otherNote.lyric = "I'm the Queen of the Night!"

But let’s do something more complex. Here I add multiple lyrics to

n1 using the Note's addLyric()

method. And instead of adding a simple String, I’ll add as a lyric the

name of the note itself and its pitchClassString.

n1.addLyric(n1.nameWithOctave)

n1.addLyric(n1.pitch.pitchClassString)

Finally, lets put the quarterLength of the note as a string with a

preface “QL:”:

n1.addLyric(f'QL: {n1.quarterLength}')

The placement of an “f” before the string

f'QL: {n1.quarterLength}’ says to substitute anything in {}

with its actual value as a string. (Remember that .quarterLength is

not a string, but a float).

As it should be becoming clear, we can always check our work with the

show() method.

n1.show()

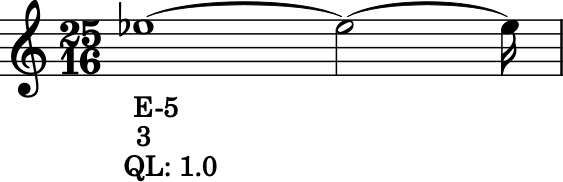

If we now edit the

quarterLength

property we can still change the Note’s Duration. But because

we already set the lyric to show “QL: 1.0, it won’t be changed

when we .show() it again in the following example.

n1.quarterLength = 6.25

n1.show()

There are many more things we can do with a Note object, but I’m

itching to look at what happens when we put multiple Notes together

in a row. And to do that we’ll need to learn a bit about the topic of

Chapter 4: Streams.